The implied author is a concept of literary criticism developed in the 20th century. Distinct from the author and the narrator, the term refers to the 'authorial character' that a reader infers from a text based on the way a literary work is written. In other words, the implied author is a construct, the image of the writer produced by a reader as called forth from the text. The implied author may or may not coincide with the author's expressed intentions or known personality traits.

Diagram files created in 2005 will load in the app today. Share with everyone. Don't worry about licenses or platforms, it just works. Powerful features. The History of Entity Relationship Diagrams. Peter Chen developed ERDs in 1976. Since then Charles Bachman and James Martin have added some slight refinements to the basic ERD principles. Common Entity Relationship Diagram Symbols. An ER diagram is a means of visualizing how the information a system produces is related.

- Looking for books by The Diagram Group? See all books authored by The Diagram Group, including The Little Giant Encyclopedia of The Zodiac, and Complete Drawing Course, and more on ThriftBooks.com.

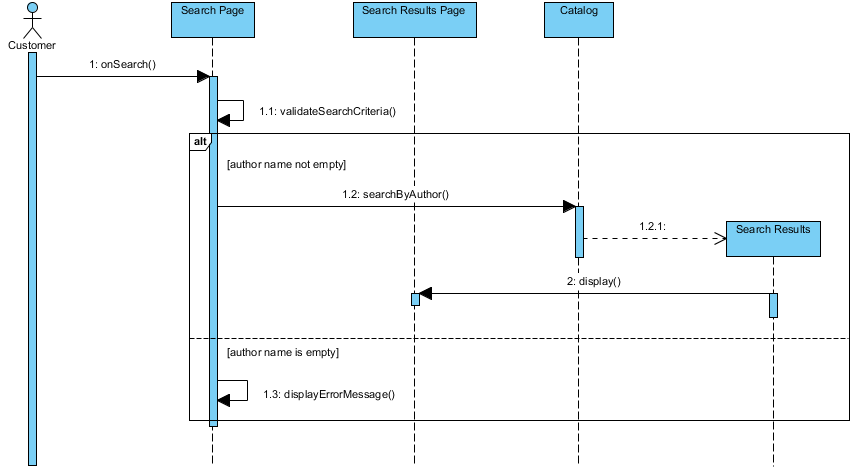

- . Sequence diagram: an “interaction diagram” that models a single scenario executing in a system. 2nd most used UML diagram (behind class diagram). Shows what messages are sent and when. Relating UML diagrams to other design artifacts:. CRC cards → class diagrams. Use cases → sequence diagrams.

- Mar 14, 2021 ER Diagram stands for Entity Relationship Diagram, also known as ERD is a diagram that displays the relationship of entity sets stored in a database. In other words, ER diagrams help to explain the logical structure of databases. ER diagrams are created based on three basic concepts: entities, attributes and relationships.

All aspects of the text can be attributed to the design of the implied author—everything can be read as having meaning—even if the real author was simply 'nodding' or a textual element was 'unintentional'. A story's apparent theme or implications (as evidenced within the text) can be attributed to the implied author even if disavowed by the flesh and blood author (FBA). [1]

History[edit]

Following the hermeneutics tradition of Goethe, Thomas Carlyle and Benedetto Croce, IntentionalistsP. D. Juhl and E. D. Hirsch Jr. insist that the correct interpretation of a text reflects the intention of the real author exactly. However, under the influence of structuralism, Roland Barthes declared 'the death of the (real) author', saying the text speaks for itself in reading. Anti-intentionalists, such as Monroe Beardsley and Roger Fowler, also thought that interpretation should be brought out only from the text. They held that readers should not confuse the meaning of the text with the author's intention, pointing out that one can understand the meaning of a text without knowing anything whatsoever about the author.

In his 1961 book The Rhetoric of Fiction, Wayne C. Booth introduced the term implied author to distinguish the virtual author of the text from the real author. In addition, he proposed another concept, the career-author: a composite of the implied authors of all of a given author's works.[2] In 1978, Seymour Chatman proposed the following communication diagram to explain the relationship between real author, implied author, implied reader, and real reader:

- Real author → [Implied author → (Narrator) → (Narratee) → Implied reader] → Real reader

The real author and the real reader are flesh and blood parties that are extrinsic and accidental to narratives. The implied author, narrator, narratee, and implied reader are immanent to the text and are constructed from the narrative itself. In this diagram, the implied author is the real author’s persona that the reader assembles from their reading of the narrative.[3]Although the implied author is not the real author of a work, he or she is the author that the real author wants the reader to encounter in the reading of a work. Similarly, the implied reader is not the real reader of a text; he or she is the reader that the implied author imagines when writing a text.

Gérard Genette uses the term focalization rather than point of view of a work to distinguish between ''Who sees?' (a question of mood) and 'Who speaks?' (a question of voice)', though he suggests 'perceives' might be preferable to 'sees', given that it is more descriptive.[4] In his 1972 book Narrative Discourse, he took issue with Booth's classifications (among others), suggesting three terms to organize works by focal position:[5]

- zero focalization

- The implied author is omniscient, seeing and knowing all; 'vision from behind'.

- internal focalization

- The implied author is a character in the story, speaking in a monologue with his impressions; 'narrative with point of view, reflector, selective omniscience, restriction of field' or 'vision with'.

- external focalization

- The implied author talks objectively, speaking only of the external behavior of the characters in the story; 'vision from without'.

Mieke Bal argued that Genette's focalizations did not describe the implied author, but only the narrator of the story.

Seymour Chatman, in his book Coming to Terms, posits that the act of reading is 'ultimately an exchange between real human beings [that] entails two intermediate constructs: one in the text, which invents it upon each reading (the implied author), and one outside the text, which construes it upon each reading (the implied reader)'. Because the reader cannot engage in dialogue with the implied author to clarify the meaning or emphasis of a text, Chatman says, the concept of the implied author prevents the reader from assuming that the text represents direct access to the real author or the fictional speaker.[6] Chatman also argues for the relevance of the implied author as a concept in film studies, a position that David Bordwell disputes.

Hans-Georg Gadamer also considered the text as a conversation with the reader.

Bibliography[edit]

Aem Architecture Diagram Author

- Juhl, P. D., Interpretation: An Essay in the Philosophy of Literary Criticism, 1981 (ISBN0691020337)

- Hirsch, E. D., Jr., Validity in Interpretation, 1967 (ISBN0300016921)

- Barthes, Roland, 'La mort de l'auteur' (in French) 1968, in Image-Music-Text, translated in English 1977 (ISBN0374521360)

- Beardsley, Monroe, Aesthetics: Problems in the Philosophy of Criticism, 1958, 2nd ed. 1981 (ISBN091514509X)

- Fowler, Roger, Linguistic Criticism, 1986, 2nd ed. 1996 (ISBN0192892614)

- Genette, Gérard, 'Figures III', 1972, Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method, translated in English 1983 (ISBN0801492599)

- Bal, Mieke, 'De theorie van vertellen en verhalen' (in Dutch) 1980, Narratology: introduction to the theory of narrative, translated in English 1985, 1997 (ISBN0802078060)

- Chatman, Seymour, Coming to Terms: The Rhetric of Narrative in Fiction and Film, 1990 (ISBN0801497361)

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg, Wahrheit und Methode. Grundzüge einer philosophischen Hermeneutik (in German) 1960, Truth and Method, translated in English 1989, 2nd ed. 2005 (ISBN082647697X)

- Sumioka, Teruaki Georges, The Grammar of Entertainment Film (in Japanese) 2005 (ISBN4845905744)

References[edit]

- ^Follett, Taylor (November 28, 2016). 'Fantastic Beasts: Amazing Writing and Terrible Representation'. Daily Californian.

- ^Booth, Wayne C. (1983). The Rhetoric of Fiction (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 431. ISBN978-0-226-06558-8. OCLC185632325.

- ^Seymour Chatman, Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1978), 151

- ^Genette, Gérard (1988). Narrative Discourse Revisited. Translated by Lewin, Jane E. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 64.

- ^Genette, Gérard (1988). Narrative Discourse Revisited. trans. Lewin, Jane E. (2nd ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 64–66. ISBN978-0-8014-9535-9.

- ^Chatman, Seymour Benjamin (1990). Coming to Terms: the rhetoric of narrative in fiction and film. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 75–76. ISBN978-0-8014-9736-0.

External links[edit]

Diagram Automotive Symbols